How the New Coronavirus Spreads and Progresses – And Why One Test May Not Be Enough

By Nina BaiIn the weeks since the outbreak, the disease has been named COVID-19 by the World Health Organization. (The virus itself has been named SARS-CoV-2 by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses).

UC San Francisco infectious disease expert Charles Chiu, MD, PhD, has been following the disease since its outbreak and provided the latest updates on what science has revealed about how the coronavirus is transmitted, what happens to someone who’s infected, and why a single diagnostic test may not be enough.

The new coronavirus is spread through droplets and surfaces.

The principal mode of transmission is still thought to be respiratory droplets, which may travel up to six feet from someone who is sneezing or coughing. The new coronavirus isn’t believed to be an airborne virus, like measles or smallpox, that can circulate through the air. “If you have an infected person in the front of the plane, for instance, and you’re in the back of the plane, your risk is close to zero simply because the area of exposure is thought to be roughly six feet from the infected person,” said Chiu.

Close contact with an infectious person, such as shaking hands, or touching a doorknob, tabletop or other surfaces touched by an infectious person, and then touching your nose, eyes, or mouth can also transmit the virus.

Chiu stresses that we do not yet have definitive data on how long the new coronavirus can survive on surfaces, but based on data from other coronaviruses such as SARS, it may be for up to two days at room temperatures.

New reports raised the possibility that the virus may be spread by fecal contamination of the environment, such as through leaky sewage pipes. Infections across multiple floors of a building due to contaminated bathroom pipes was previously demonstrated for SARS coronavirus.

It’s probably less deadly than SARS, more deadly than the flu.

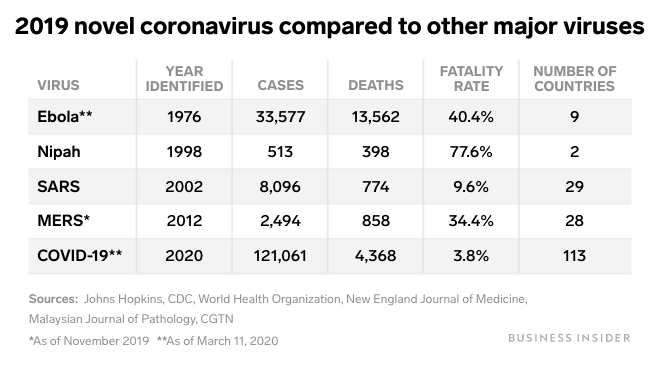

The latest estimates based on the reported number of cases and deaths suggests the death rate is about 2 percent. For comparison, SARS had a death rate of about 10 percent and seasonal influenza has a death rate of 0.1 percent.

However, according to Chiu, the actual death rate of the new coronavirus very well may be lower than 2 percent because the total number of cases likely has been underreported. Not all cases are promptly identified, especially in Wuhan, where medical services are stretched thin, and there have been documented cases of asymptomatic and minimally symptomatic transmission, which are harder to identify and track.

“I believe that the actual calculated death rates will go down over time, perhaps to less than 1 percent” said Chiu.

This is how the disease progresses: (Day 7 is the worst.)

“From published reports, we do now have a better sense of the overall time course for the disease,” said Chiu. Once a person is exposed and becomes infected, the incubation period before the onset of symptoms is about five days, although this can vary from two to 11 days. Flu-like symptoms are often mild at first and some patients recover without the symptoms becoming more serious. But for a subset who get worse, day four after the onset of symptoms is usually when they seek medical care because they develop shortness of breath and early pneumonia, said Chiu, and they may become critically ill by day seven. After day 11, most patients who survive are on their way to recovery.

Treatments are still experimental and unproven.

No drugs or vaccines yet have been proven effective against the virus, but some experimental treatments are being tried. These include Remdesivir, an antiviral drug that was originally developed for Ebola, which was given to the patient in Washington State and is being given to some patients in China, said Chiu. Other groups are trying various combinations of antivirals, including anti-HIV drugs. In the absence of a proven drug therapy, patients receive supportive care, such as supplementary oxygen, fluids, and antibiotics to guard against secondary bacterial infections.

Even those who recover from COVID-19 might not be immune forever.

“Unfortunately, we don’t know yet whether or not the body’s immune response would protect you from subsequent infection,” said Chiu. It is known that exposure to the four seasonal human coronaviruses (that cause the common cold) does produce immunity to those particular viruses. In those cases, the immunity lasts longer than that of seasonal influenza, but is probably not permanent, said Chiu.

A single negative test may not rule out infection.

The currently available diagnostic test is a PCR test developed by the CDC, which looks for RNA from the virus. However, hospitalized patients infected with the new coronavirus can have test results that vary from day to day because the amount of virus produced by the body can change throughout the course of the illness, said Chiu.

Repeat testing may be necessary to determine if a suspected person has been infected or when a patient is no longer infectious. “The take home message is that a test that looks at a single time point is not sufficient to rule out infection,” said Chiu.

Evidence from the case in Washington State also suggests that the severity of the illness does not necessarily correlate with levels of the virus in the body – meaning someone can be very infectious without seeming very sick. “That’s why there’s concern that patients who are minimally symptomatic may be fueling the outbreak simply because they don’t feel sick enough to go to the hospital,” said Chiu.

Chiu’s lab, in collaboration with the startup Mammoth Biosciences, is developing a rapid diagnostic test that could more quickly and widely monitor for the disease. The new test is a color-changing test strip that uses CRISPR to detect viral RNA and can be run in 30 minutes to an hour. “We’ve been able to run this rapid test on both control samples and patient samples and it appears to be working,” said Chiu. He hopes to optimize the test so that it can be run by anyone and deployed in low-resource areas.

Health care workers are taking maximal precautions when treating COVID-19 patients.

To protect against infection by the new coronavirus, health care workers wear personal protective equipment such as gowns, gloves, face shields, and N95 respirator masks when they are in the same room as a patient who is in isolation. “All health care personnel get regular fittings of N95 masks to ensure that they are worn properly,” said Chiu. These precautions are meant to protect against contact, droplet and airborne transmission. The additional airborne precautions are taken in the health care setting because some medical procedures, such as endotracheal intubation, may cause secretions to be aerosolized. Chiu said that, per CDC recommendations, items brought into the room are preferably disposable, or if not, are disinfected before being removed from the room, and after the patient is discharged from the hospital, the entire room is disinfected.